Coté

2025 IT Budgets See 5.5% Increase as CIOs Invest in AI and Cloud - “With a projected 5.5% increase in IT budgets, the year ahead is set to focus heavily on artificial intelligence (AI) and cloud computing."

Five Lessons Learned From a Lifetime of Platform-as-a-Product - Text version of a good talk.

How DevOps can come back from the dead, and why it must

The DevOps community is running on fumes and at the lowest point in mindshare and interest that it’s ever been at. This is stupid. The practices, tools, and mindset of DevOps are vital to how most organization run their software1 and DevOps has improved the way the software we use everyday is built and run, improving all of our lives. If DevOps wasn't a thing, the world of software would be worse and each day would be a little more tedious because the apps we depend on would be worse.

Here's what I think DevOps needs to do to come back from the dead:

(1) Steal back the flame from platform engineering

Developing software and building digital capabilities is becoming ever more complex. By 2026, 80% of large software engineering organizations will establish platform engineering teams as internal providers of reusable services, components and tools for application delivery - up from 45% in 2022. Gartner, circa 2024.

"Platform Engineering," is fine, but creating it as separate, new method of work has done a disservice to DevOps. Shoving DevOps into a grave was also a bit rude.

Platform engineering was a very well done marketing strategy to establish a new market for a handful of portal vendors to start working in. All of us joined the momentum of platform engineering. I have done it many times, and probably still will!

Much like The 12 Factor App, a piece of brilliant technical marketing, platform engineering has actually become its own, legit thing now. But, that early strategy of stealing the sun-light from DevOps made platform engineering seem like more than it is. Platform engineering is just DevOps with one small thing: adding in product management.

The rest of platform engineering is just adding new tools to the DevOps toolchain: primarily internal developer portals and all of the work and tooling that goes into making Kubernetes usable for developers. Over the next 12 months, platform engineering is going to take hold in "enterprises" (see Gartner prediction above), which is what I call large organizations that are not tech companies: you know, IT normies. There's early use here-and-there in enterprises,2 but not at the scale of DevOps, or even cloud native (you know, architecting your applications in containers).

The DevOps community has to take over, gobble up, or otherwise “ride” the platform engineering wave or get drowned by it, lost in the deep like some ancient city. It's too late to reverse the name. And, really, "platform" as a name is incredibly valuable and descriptive, and "platform engineer" is a fine synonym for "DevOps engineer."

The job title might even do a good job to clean house on what exactly a "DevOps engineer" is. This is the case with DevOps in general: it's become so dominate that “DevOps” has started to mean most anything, and everything related to building and running in-house applications. This is not good!

(2) DevOpsDays should be renamed to Platform Days

When suggesting such a thing, one must always begin with praise.

The community-driven, global DevOpsDays organization is one of the most unique assets in the IT world. At the moment, there's nothing like it: a vendor-independent, volunteer-led organization focused on industry best practices that holds regional events to educate and enrich the community.

Let me do some boosterism here:

Being vendor-independent is important for two reasons. First, it means the content is actually practical and "true" without the bias of a commercial agenda. Second, it means that all vendors feel comfortable sponsoring DevOpsDays. Vendors are incredibly important to the DevOps community. They're the ones who have funded its existence! If the overall community and DevOpsDays was owned by a single vendor or an oligopoly it wouldn't have been successful nor valuable. Vendors have an agenda to sell their products and their market category (people who sell on-premises software want to show buyers why private cloud is the best, people who sell public cloud software want to show buyers why on-premises software is better, people who have new tools of monitoring and log management want to explain to you why the old ways suck - shocker!). Vendor's budgets also come and go at the whim of their business, new technologies, and macro-economic headwinds. One year, the company is focused on growth at all costs to drive company valuation, the next year the company is focused on cutting costs because a PE firm bought them. One year, money is cheap, the next year money is scarce. One year, DevOps is important, the next year generative AI is important. Budgets shift! In short, depending on vendors to support an ongoing, multi-decade community is risky.

The volunteers are the ones, then, who make it all happen. The passion that DevOpsDays volunteers have for the DevOps community and event is extremely rare in other parts of IT. Even the agile community doesn't seem to muster enough energy to put on so many conferences. I don’t think application developers can be bothered to look up from their IDEs. There are regional meetups and user groups in IT, sure, but I don’t think there’s anything close to the scale of DevOpsDays. While my overly utilitarian, cold heart might ache at all the "culture" talk in the DevOps community, that vibe is incredibly real and important: it becomes part of the identity and lives of these volunteers. I don't want to see that lost, and it's a huge asset that the IT community should cherish and protect.

Focusing on best practices means that the talks, workshops, and discussions at DevOpsDays are focused on continually improving the IT community. There have been four, maybe even five stages of DevOps over the past 15+ years. The DevOpsDays talks focus on what the DevOps community needs help with at the time. You can see this in the community's shifting from automation (infrastructure as code, immutable infrastructure, Puppet, Chef, etc.), to monitoring and management (observability, chaos engineering, etc.), to culture (how people work, the mindsets that lead to good outcomes and good lives), to filling the usefulness-gap created by people's over-enthusiasm for Kubernetes, to the present.

DevOpsDays are in-person which is the most effective way to educate the community and keep it thriving. More than many other in-person events, the edge that DevOpsDays has is that the events are regional. They’re all over the world. This means that people in the DevOps community don't have to pay to travel, and if they do, it's usually just an hour or two to go to a nearby city. Compare this to one, large event a year in Las Vegas or Barcelona. The audience and community reach for DevOpsDays is so much larger and, thus, more effective.

The survival of DevOpsDays is more important than the survival of the name DevOpsDays. Because the platform engineering community successfully stole so much of the mindshare, they've sucked much of the sponsorship money out of the DevOpsDays. Worse than redirecting the money is drying the money up all together. Marketing budgets are tight now-a-days (I'm not sure why: vendors want to sell more than ever) so the people controlling event sponsorship money is looking for an excuse to cut costs. And, of course, there’s the redirection that platform engineering, drawing attention and therefore people away from DevOps.

There is currently no platform engineering set of conferences like DevOpsDays. PlatformCon is a good, online conference. I enjoy the recordings, have presented at them, and have encouraged other people to present. The PlatformCon crew is building up momentum for more in-person events (see all the regional group on their above page) - this is great! Good for them! Yay! RIP-TAYLOR-CONFETTI-BLAST!

But it will take years to replicate the reach and assets that the DevOpsDays community has.

I know it feels weird to the DevOpsDays people - it feels weird to me! - but renaming DevOpsDays to PlatformDays would solve a lot of problems quickly. Maybe the PlatformCon community could even merge with DevOpsDays, joining up the benefits of both. I don’t know. Maybe.3

(3) DORA should focus less on metrics and more on practices

DORA is probably the most important marketing asset DevOps has and has had. And it's a genuinely useful tool! DORA’s work is what helped spread DevOps into the mainstream, all those "enterprises.” And the annual cadence and DORA community has helped DevOps evolve, and kept it alive.

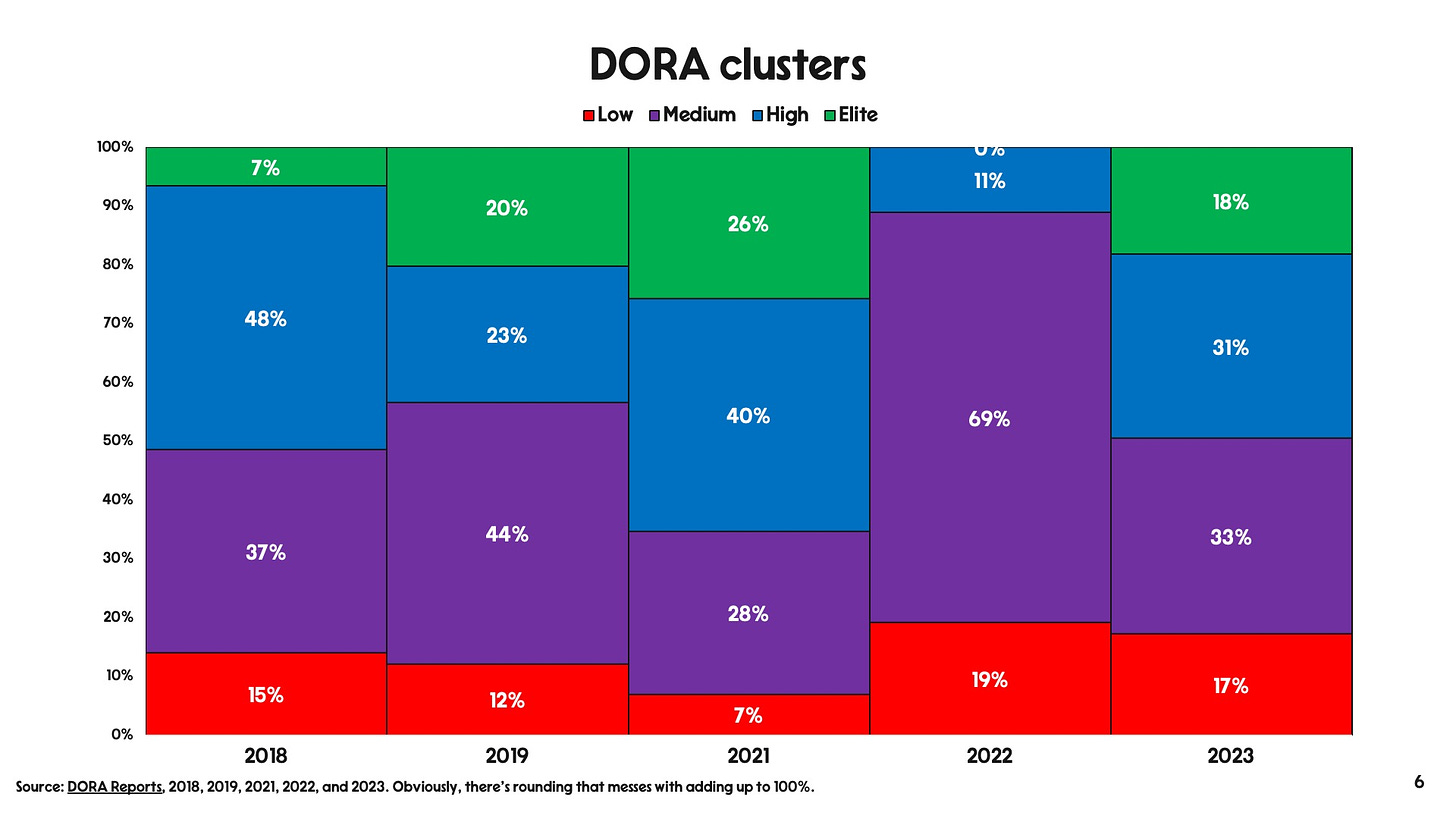

The problem DORA has now is that most people focus only on the four DORA metrics. Common lore is that those enterprise normies don't look beyond the four metrics. This extends to DORA's annual clustering of elite, high, medium, and low performers: these are rankings. Those are just small parts of the overall knowledge in and utility of DORA. I don't think this short-sightedness of DORA users is intentional, or even conscious. It's how just people work.

Whenever you put metrics and rankings in front of a corporate-human, eventually they'll focus most of their intention on upping their ranking. People do this because they think that being successful means being ranked high, getting a good score/grade. This is because that's how rewards are given in most organizations! Gaming metrics is the most rational thing for a person to do in most organizations. Each year, DORA refines high-grade fuel for this way of working and thinking.

Just as it's not really the fault of the users, it's not really DORA's fault either. But, DORA can help people do better by re-orienting their annual work.

First, the value of DevOps practices are not really in dispute. We all know that they're good. As with flossing, we all know that we should do the practices. DORA shouldn't stop gathering and analyzing these metrics, nor reporting on them.

What DORA needs to do is move the focus reporting on the actual practices people follow. The activities they do day-to-day, the tools they use, that lead to the great results and clustering.

Of course, DORA currently cover this, but over the years the reports have focused more and more on a discussion of the survey and mechanics of the research rather than actions to take. This is fine! I get it - I have an engineering mindset and I would rather tell you about the internals of what I build, how I did it, and, most of all, what's cool about it. But the DORA-users need a tool. They need to know what to do, not why they should be doing it.

Sure, there's a danger that the users apply tools the wrong way, and you end up with a similar trap of focusing just on the four metrics. But, I mean: let's have a little more faith in people, and DORA’s ability to avoid that.

Let's also take a lesson from Extreme Programming. Extreme Programming is incredibly prescriptive. And, while I don't want to speak on behalf of the priests of that community, over the past few decades there's been a latent operating principle of using Extreme Programming: start with following all of the strict practices, learn what works and doesn't work in your organization, adapt the practices, and start the loop over again. That is how the DORA practices should be applied, and it should be the mission of DORA to make it happen.

In the most recent DORA report (2023) an easy to use discussion of these practices doesn't start until page 81 (out of a total report size of 95 pages). I confess my laziness here and apologize if it resulted in error, but after a few quick flips, I couldn't even find where the practices are covered after flipping through the 77 pages of the 2022 report, the 45 pages of the 2021 report, and had to go all the way back to 2019 to find this on page 31 of 82 pages:

…and page 57 to find the equally valuable this:

There's a snark in the DevOps community that the problem with Accelerate is that everyone who read it came across the four metrics on page 17, declared that they had all they needed, and then closed the book. Well, how about we put a discussion of practice - these very charts - on page one, or, at least page 9.

People in enterprises who are struggling to get better at software need this kind of material: easy to understand, focused and quick, and possible to put into place practices. How do you ensure you floss everyday? First, buy some floss. Second, put it where ever you brush your teeth. Third, notice when you do it and don’t do it. Fourth, keep trying to do it better each day. Life-hack: put it on your desk and turn off the camera when you're bored in a dumb Zoom meeting you can't get out of, and floss. You could also keep the camera on.

The "model" (as I think DORA calls it) is there, and it's even nicely done on the DORA community site (see the figure at the beginning opening of this section). What I'm suggesting is that it should the primary, the first focus of each report. When you email around a 45 to 95 page PDF in enterprises you have one shot to get people to read it and benefit from it. They're looking for the most effective tool they can use right now to achieve whatever goals they have. That practices chart is the tool they're looking for and it should be the first thing they see in the 30 seconds they're going to spend on that PDF. The rest of the work is great, valuable, and hard to do, but those are the "backup slides" that you'll use once you get people's attention and show them what you're proposing.4

We don't need further proof that flossing is good, nor to be told that people who floss have elite teeth. We need to know the mechanics of flossing and how to build a system that lets us put in place continuous flossing.

(4) DevOps should add product management for infrastructure

I give platform engineering a hard time because the people who launched it tried to push the DevOps community in the grave. Or, I don't know, maybe they were just having fun with the headline. Har, har, har…good one.

But, rasing the prominence of product management is an incredibly valuable thing that the platform engineering community has done. And it’s why I think it’s a good, helpful body of work.

The ideas of product management - identifying your customers/users and using, their problems/jobs to be done, crossed with what is technically feasible, and using feedback loops to continuously build a product that best solves their problems…with software - haven't been a large part of the DevOps community. The platform engineering community frames their work as building platforms for application developers, treating them as "customers," and, therefore product managing infrastructure for application developers.5

Sure. Absolutely. Without a doubt. The DevOps community has wanted that outcome and worked towards it. It's right there in the name: Dev! But product management as a practice hasn't been a focus in the DevOps community. It should be! There is a-funny-because-it's-true joke that there are very few devs at a DevOpsDays conference.6 The same is true for the community as a whole.

The good news here is that product management is one of the most understood, well documented, and proven methods of working in software. Thus, from a regular person's perspective - those people enterprises - product management is straightforward and learnable.

Despite product management being easy enough to learn, I think it’ll be incredibly difficult for enterprises to add product management to their infrastructure/DevOps/platform groups. They’re going to need help, and the DevOps community has a proven track record for such tough work.

Some of the people who introduced product management into infrastructure ("platforms") over the past ten years have done a great job grafting their term of art, “platform as a product,” into platform engineering. And it's stuck! I wish this had happened in the DevOps community, but because the platform engineering fig vines took over, it didn't.

Well. You know. We should bring product management into the DevOps world.

For example, DORA could start incorporating it into their studies. While product management is understood for applications, there's not a lot of work on applying it to infrastructure (yes, again: "platforms," if you prefer) and developer tools. Us vendors know about it since it’s our business, but figuring out how to do it in enterprise infrastructure (or even apps!) isn't much studied. DORA can do that, and it'd help clear out some of those vines if they did. (I know the Puppet study-surveys are going for it, so good on them!)

In fact, I'd go as far to say that product management is the missing piece for the wider success of DevOps.

(Now, if you wanted to be clever, you would think this: platform engineering is focused on developers and product manages for them. DevOps will do that, of course, but what a DevOps person will tell you is operations people are also customers [and maybe security people if they behave]. Why not product manage for ops too?)

I will be sad

Listen: I know! I hear you.

But, I'm not saying your efforts are wasted - it's all good stuff. We just need to do more. We need to adapt and change. Fast feedback loops, continuous learning, and changing to do what works are core principles of DevOps. This is what I'm seeing in the feedback loops and the theories I have for how to get better.

I give a huge, massive, rainbow-smelling shit about the DevOps community. It's been a positive force in my career and life. Many of my friends are in the DevOps community and going to DevOpsDays is how I see them. It’s fun! DevOps has also had an important, large impact on how the world builds and runs software. And not just “hats on cats” apps, but apps that you and use everyday to run our lives.

There's a lot of existential malaise going on in the DevOps community, especially among the most enthusiastic and committed members of the community. Some (many?) of the original DevOps community members have drifted out of the community, and will sort of roll their eyes over the whole thing over drinks. There isn't a better community in IT than the DevOps community - it's managed to remain kind, helpful, and nice. I'll be sad if we can't keep it alive and thriving.

Logoff

I guess what I’m trying to say is: DevOpsDays Antwerp was good. It was nice to visit with everyone and see some great talks.

Lazily aggregating analyst surveys, I’d say that about half of the relevant IT people “do the DevOps” in the surveyed organizations. And, if you look at the progress made in things like speeding up release cycles, things have improved a great deal even since just 2018. DevOps is successful, so much so that we don’t really think of it much anymore: “this is water” and all that.

Please, oh please, ask me about the VMware Tanzu by Broadcom customers who’ve been doing platform engineering for five to ten years and how the products that help pay my monthly bills have made it possible. I’m just waiting, right here. Pick me, pick me! Still here. Yup.

I mean, if Gene Kim is going to rename his DevOps event, it’s probably OK and it might even feel good.

The irony of this post being well over 2,700 words is not lost on me. More now that I wrote this footnote.

Here are three great places to start with exploring what product management means for infrastructure: (1) "Platform Engineering at bol: Unveiling Insights from Adopting a Web Portal," Onno Ceelen and Roy Triesscheijn, June 2024. (2) “Boosting Developer Platform Teams with Product Thinking,” Samantha Coffman, March 2024; (3) “Designing for Success: UX Principles for Internal Developer Platforms,” Kirsten Schwarzer, March, 2024. There’s also an emerging understanding that you have to market and even devrel your internal platform. That’s something equally kind-a-sorta not covered in the DevOps community.

As a rule of thumb, you can tell that someone is new to the DevOps community if they ask how many developers are in the room and especially if they start addressing developers, “well, as the developers in the room know…”

Beyond mystic management mind-games

Searching for Cheap Tricks

The amount of AI content and conversations out there is getting exhausting. It’s almost as bad as the burbling font of platform engineering content that gets rewritten and published each week. The below RAND paper and commentary got me thinking though: a lot of the AI talk is just talk about applying new technologies in general.

We are still really bad at the basic task of communicating requirements to developers, checking in on their work and seeing if they’re solving the right problems in a helpful way…and even knowing what business problems to need attention in the first place.

Here’s an email I wrote to a friend on this:

Re: my prodding to figure out cheap tricks for getting organizations to improve how they use computers, this paper has a few theories of why AI projects fail. I feel like you could do a search and replace for "AI projects" to just "IT project" and the same could be said. The core, non technical problem is two sided:

(1) getting non-technical leadership to understand what AI can do, how much effort it takes to do the work, and most importantly how to properly set the requirements: making sure you solve the right problem in the right way. This last part is the mystic "understand what you're doing, the point of it, the why's of your business." Like we were talking about last night in the backstreets of Antwerp, my theory here is that if you asked most people in a business "how does the business operate and function each day?" they would have poor answers, let alone answers that an AI could do anything with, or that programmers could do anything with.

(2) the technical people are unable to "speak the language of business" and get the people in #1 to "speak the language of IT." I'm sure this is a lack of communication, facilitation, and interpersonal skills ("managing upwards"), but it probably results in the tech people not pushing back enough and drilling down to get the non-tech people to be helpful. This is the pesky thing of consultants always saying "before we talk solutions and projects, let's take a step back and examine what you really want." People are eager to fix/improve the problems, and don't often question if they're solving the right problem, nor understand the tools available to solve it. (Including the tool of continuous learning which would say "we have to use a tight-feedback loop to learn how to solve the problem).

It all amounts to introducing an ongoing "culture" of finding and understanding the problems you're solving, and a similar process of "leadership" frequently checking in to see if the tech people are getting closer to solving a useful problem, or if they're straying away from the original requirements.

One of original goal of agile software development was to address these problems: “business IT alignment” as we sometimes called in the 2000s.” On the one end, Extreme Programming had a concise, clear cookbook to follow. I like these prescriptive, “do this” approach to corporate improvement. They’re a collection of “cheap tricks” you can start applying.

However, the “fix” is to change the mindset of the company, from management to worker, to always be curious and on the hunt for how to do things better, “continuous improvement.” There isn’t always a way to do things better, and you also have to spend most of your time actually doing things.

But, there’s at least two things that most organizations could be better at:

Understanding what they do, the job to to be done, and how their organization does that - I have a feeling that if you asked most people, tops to bottom, at an organization “how do things really work around here?” you’d get mixed results, most of them only part of the overall picture. Can you draw out and end-to-end flow of all the activities it takes to deliver the product or service to the customer?

Spotting when to experiment with changes. This is applying Toyota kata and all that. The mystic version of “continuous learning” is that you’re always on the lookout for learning and improvement. But, you also have to actually do the work. You have to check out people at the grocery store, put the Fedex letter into a person’s hands, send out a plumber at the right time to the right place to unclog a sink (and then they need to unclog it), transfer money between two accounts, etc. When is it OK to stop “doing things” and work on improving things? That’s a very hard “stop the line” call to make.

I want to find a way to combine the mystic management mind-games of most corporate improvement and transformation talk with “cheap tricks” that get people to start improving and keep improving.1 This is something like “the habit of building habits.” It’s all well and good to talk about “habit stacking” and tell people that they need to establish new habits and routines. Yes, but how do I start the habit of starting habits?

Once the people in an organization have gone through the mystic experience of asking “why” or even discovering their customer’s milkshakes, what are the daily tasks and routines they do? What tools do they use? How do they actually do the work? What are the cheap tricks they can start using to be better?

Relative to your interests

Moonbound Revisited - “Several decades ago, the semiotician A. J. Greimas claimed that all stories are comprised of six actants, in three pairs: Subject/Object; Sender/Receiver; Helper/Opponent.”

The Forgotten Surrealist Painter Who ‘Didn’t Have Time to Be Anyone’s Muse’ - “In contrast to the tendency of Surrealism’s male artists to depict women as thin, young, fragmented, static, and perpetually naked muses, Carrington’s women fell across a spectrum: often very old, powerful and threatening, in a state of action and transformation.”

How Platform Engineering Enables the 10,000-Dev Workforce - Vendor survey overview.

How the buildings you occupy might be affecting your brain - “Could bad architecture also be contributing to the development of neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders?”

Is AI a Silver Bullet? - “This is the trade off we have seen before: eliminating the accidental complexity of authoring code has less value than we think because code spends most of its time in maintenance, so the maintainability of the code is more important than the speed to author it.”

The Root Causes of Failure for Artificial Intelligence Projects and How They Can Succeed: Avoiding the Anti-Patterns of AI, RAND paper - As ever, communicating the requirements and the problem to be solved to IT is difficult and often results in solving the wrong problem, at least in the right way: “In failed projects, either the business leadership does not make them- selves available to discuss whether the choices made by the technical team align with their intent, or they do not realize that the metrics measuring the success of the AI model do not truly represent the metrics of success for its intended purpose. For example, business leaders may say that they need an ML algorithm that tells them the price to set for a product–but what they actually need is the price that gives them the greatest profit margin instead of the price that sells the most items. The data science team lacks this business context and therefore might make the wrong assumptions. These kinds of errors often become obvious only after the data science team delivers a completed AI model and attempts to integrate it into day-to-day business operations.”

Why “AI” projects fail - “And we’ve been doing this for decades now, with every new technology we spend a lot of money to get a lot of bloody noses for way too little outcome. Because we keep not looking at actual, real problems in front of us – that the people affected by them probably can tell you at least a significant part of the solution to. No we want a magic tool to make the problem disappear. Which is a significantly different thing than solving it. Because actually solving a problem includes first fully understanding the reasons for the existence of the problem, reasons that often come back to an organizations’ structure, their – sometimes inconsistent – goals and their social structure in addition to actual technical issues.” And: “AI is so good at writing summaries of all the meetings I can then have summarized afterwards to understand what was going on” says that your organization has probably too many meetings that are not structured well and that you don’t think that understanding why people say a thing, how they present their case is important (which makes you a bad manager).”

Per Request

Wastebook

“Progressive doomerism.” Here, but, interestingly it was my perplexity.ai summarizer that came up with that phrase which did not exist in the article.

“I want to stay little like this. I don’t want to get bigger.” My four year old.

“Dystopian hod-rod races.” Apple Music summary of Liquor in the Front.

Similar to “resume-driven development”: “Given the demand for new AI projects, interviewees reported prioritizing projects that grab headlines, improve reputation, and increase institutional prestige. We refer to this as activity prestige, which is the amount of positive attention given to some projects based on the public demand for those projects' outcomes.” Here.

Logoff

I’m in Antwerp for DevOpsDays Antwerp. This is the 15th year anniversary of DevOpsDays, so I wanted to attend. I’m lucky that they accepted a five minute talk from me as well. In the talk, I’m trying to answer the question “has DevOps made things better?” I do that by looking at changes in the DORA clusters, but more importantly, changes in how those clusters are made (thanks to some help from Steve Fenton and Nathen Harvey understanding how that is all done and, thus, a more accurate y/y analysis).

And, then, of course, I give some advice on what the DevOps community should focus on now. These are just two points I talk about a lot here: (1) make sure you actually have build automation in place, because it seems like many people don’t, and, (2) stop building new platforms and just use pre-built ones. If there was a third common theme for me, it’d probably be something like “start the practice of product management” this despite how difficult, even impossible, that seems.

//

There are two Brueghels in Antwerp, at the Museum Mayer van den Bergh. First, it’s a great museum if you’re into Flemish and Dutch golden age paintings. The building itself is a nice Netherlands canal house style building. The two paintings are Mad Meg and Twelve Proverbs.2 Here is Mad Meg:

Seeing pictures like these is much different in real life than online or even in books. It’s not that much different so as to be divine or anything: you just see some new things like textures and your field of vision either gets bigger or smaller. For example, with Mad Meg, you can really get in there and study the countless micro-scenes. In contrast, with Twelve Proverbs, you can see how basic and simple the pictures are; unlike the Brueghels most everyone knows, these pictures are not chaotic and “alive.”

Anyhow.

If you like that kind of thing, you should check out on of my favorite books, Short Life in a Strange World. If that book is a good fit for you, while it’s a bit mystic, it’ll help you enjoy “art” in new ways. If you just want the cheap tricks, check out the equally good Art as Therapy.

As more examples, there’s some general IT/business alignment cheap-tricks discussed in this excellent video.

It’s hard to find a list of the 12 proverbs. But, later in life he did a much larger picture, in the Brueghel style you’d expect, of Netherlandish proverbs which are much better documented.

Is AI a Silver Bullet? - “This is the trade off we have seen before: eliminating the accidental complexity of authoring code has less value than we think because code spends most of its time in maintenance, so the maintainability of the code is more important than the speed to author it."

How the buildings you occupy might be affecting your brain | Psyche Ideas - “Could bad architecture also be contributing to the development of neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders?"

The Root Causes of Failure for Artificial Intelligence Projects and How They Can Succeed: Avoiding the Anti-Patterns of AI | RAND - As ever, communicating the requirements and the problem to be solved to IT is difficult and often results in solving the wrong problem, at least in the right way: “In failed projects, either the business leadership does not make them- selves available to discuss whether the choices made by the technical team align with their intent, or they do not realize that the metrics measuring the success of the AI model do not truly represent the metrics of success for its intended purpose. For example, business leaders may say that they need an ML algorithm that tells them the price to set for a product–but what they actually need is the price that gives them the greatest profit margin instead of the price that sells the most items. The data science team lacks this business context and therefore might make the wrong assumptions. These kinds of errors often become obvious only after the data science team delivers a completed AI model and attempts to integrate it into day-to-day business operations.”

Why “AI” projects fail - “And we’ve been doing this for decades now, with every new technology we spend a lot of money to get a lot of bloody noses for way too little outcome. Because we keep not looking at actual, real problems in front of us – that the people affected by them probably can tell you at least a significant part of the solution to. No we want a magic tool to make the problem disappear. Which is a significantly different thing than solving it. Because actually solving a problem includes first fully understanding the reasons for the existence of the problem, reasons that often come back to an organizations’ structure, their – sometimes inconsistent – goals and their social structure in addition to actual technical issues.” And: “AI is so good at writing summaries of all the meetings I can then have summarized afterwards to understand what was going on” says that your organization has probably too many meetings that are not structured well and that you don’t think that understanding why people say a thing, how they present their case is important (which makes you a bad manager)."

Moonbound Revisited - “Several decades ago, the semiotician A. J. Greimas claimed that all stories are comprised of six actants, in three pairs: Subject/Object; Sender/Receiver; Helper/Opponent."

The Forgotten Surrealist Painter Who ‘Didn’t Have Time to Be Anyone’s Muse’ - “In contrast to the tendency of Surrealism’s male artists to depict women as thin, young, fragmented, static, and perpetually naked muses, Carrington’s women fell across a spectrum: often very old, powerful and threatening, in a state of action and transformation."